The question from the five-year-old in the back seat on the way home from the hospital has etched itself into dad Rune’s memory forever.

One night in September 2017, Rune Lunde is walking slowly round a running track in Randaberg. It’s a mild night in late summer, with not a breath of wind. The moon has risen, you can hear quiet voices murmuring here and there, and see firebowls and lights twinkling, making the night feel even milder.

A man comes up alongside Rune. He’s also out walking – maybe for himself, maybe for someone else. They get chatting, lap after lap, forgetting the time and place. The man tells his story, but would also like to hear Rune’s. What load is he carrying? Why is he taking part in the Norwegian Cancer Society’s Relay for Life?

It’s 8 May 2001. Liberation Day. Norwegian flags are everywhere. Everyone who is old enough remembers the feeling of relief on that day in 1945, the realisation that life was slowly but surely going to get back to normal, that they would be able to relax and breathe out.

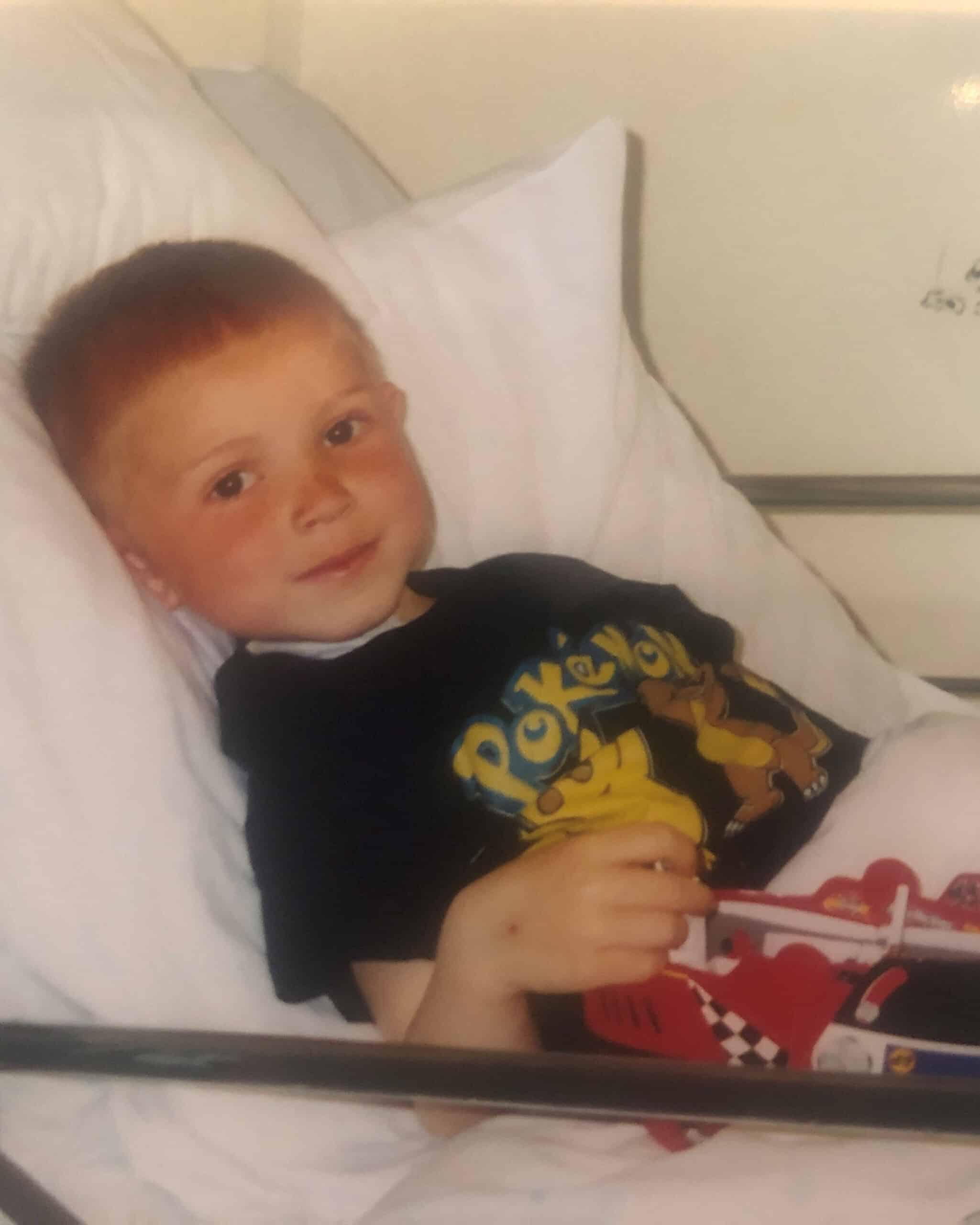

Today there’s a car driving through these memories. With a little four-year-old boy sitting in the back seat. He knows nothing about the war, but he knows that something is ravaging his body.

His name is Vegard, and he is sick. Mum Ellinor and dad Rune have suspected it for quite a while. They’ve been to the doctor so many times, but their questions have never been answered. But now their suspicions have been confirmed. The listlessness, the swollen abdomen, the thin arms and legs now have an explanation: cancer.

The contrast to the joy, peace and freedom in the flags waving outside the car windows is stark.

Vegard has cancer

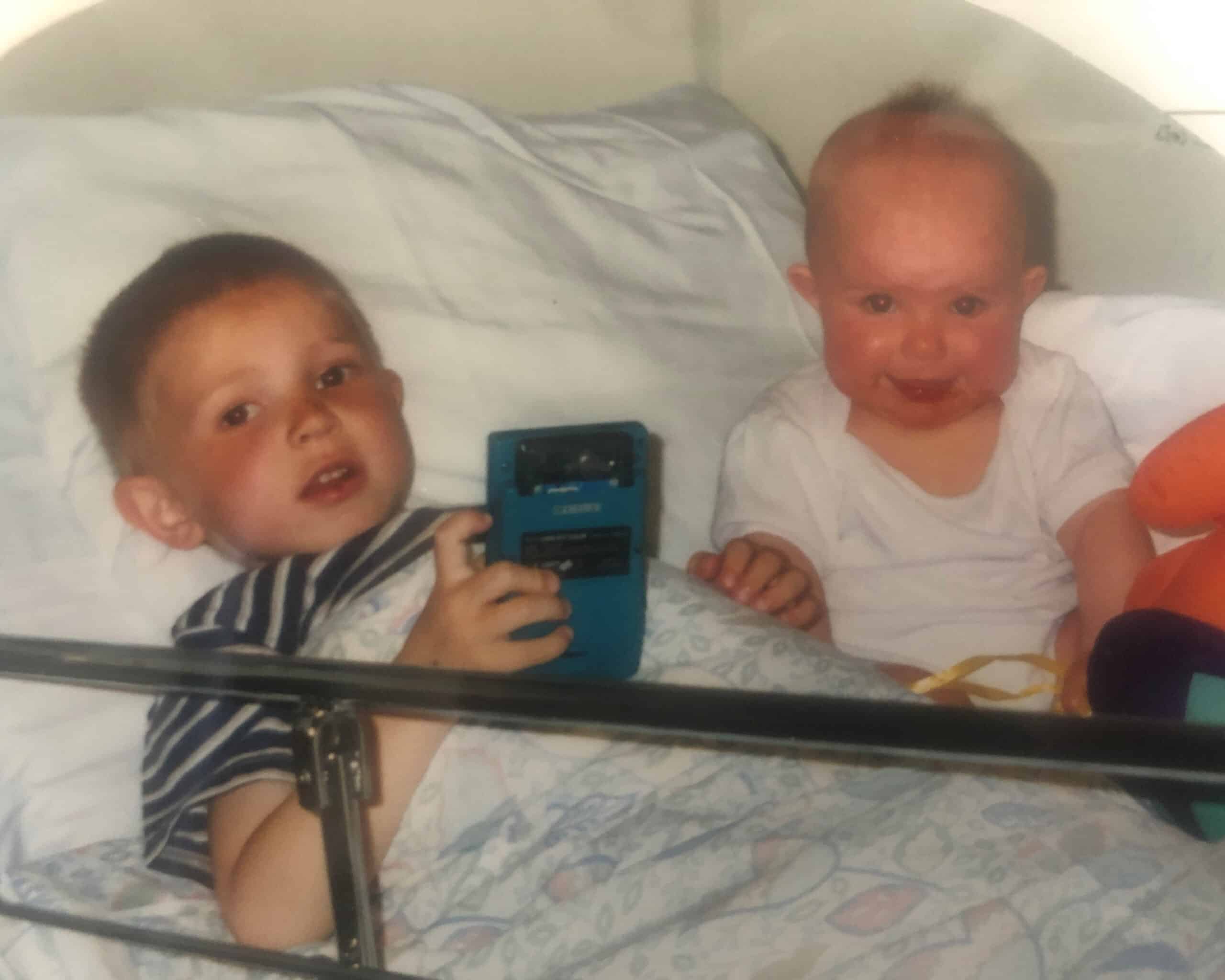

When they went on holiday to a cabin at Easter, Vegard had to lie down more or less the whole time. After endless appointments, Ellinor had to take her son to the doctor once again. That was on 8 May; she was carrying four-year-old Vegard on one hip, and his eight-month-old little sister on the other. After the appointment, Ellinor received a phone call telling her to drive straight to the hospital in Stavanger. She arranged a childminder for the baby and tried to get in touch with Rune, who was at work in Oslo.

In the back seat, Vegard asked why it was everyone’s birthday today.

Things started to move quickly. The following morning, the family was flown to Haukeland.

– We handed the two girls over to some nurses, Ellinor explains.

– Vegard went straight onto dialysis. If he hadn’t got that treatment, he would have died, Rune said.

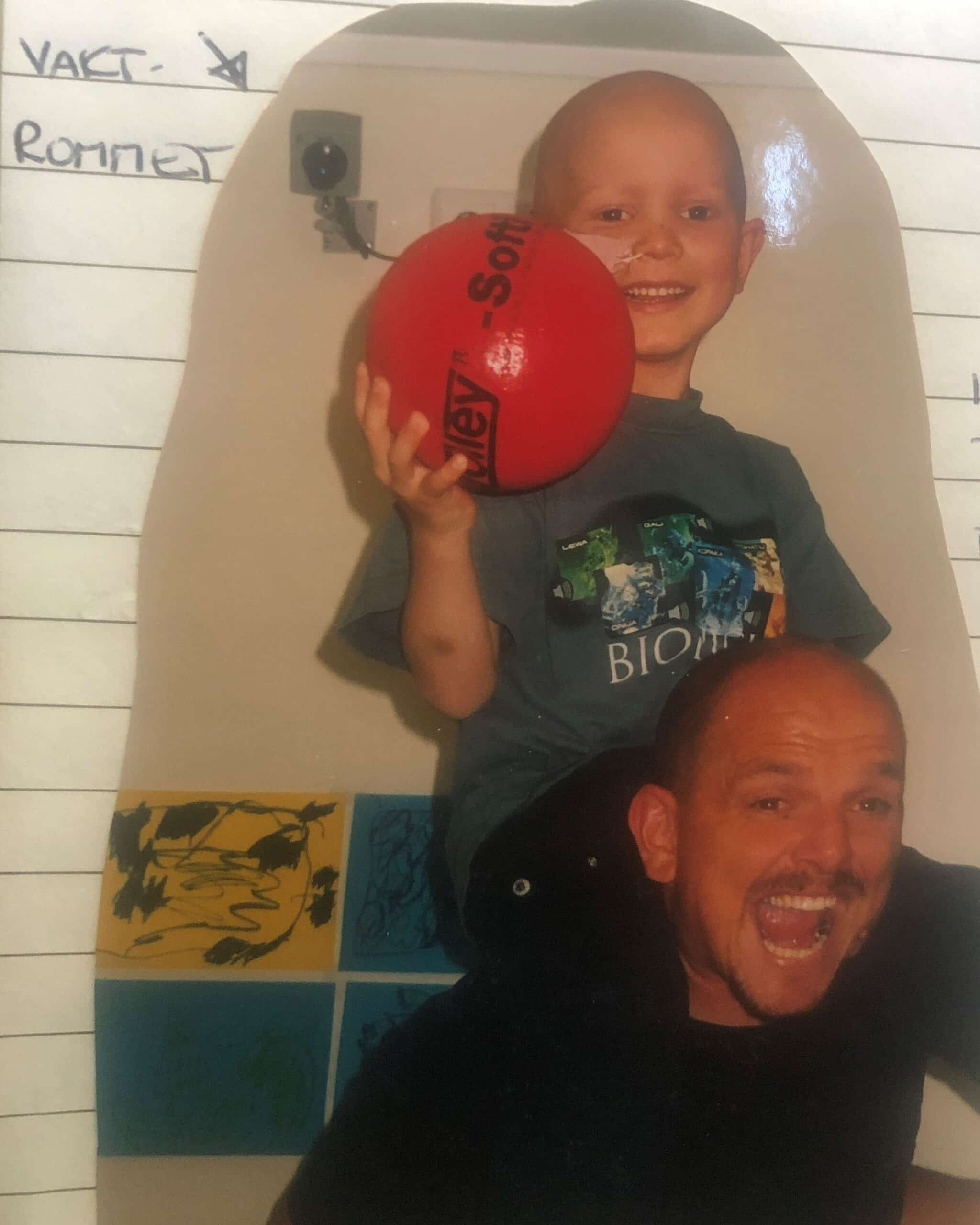

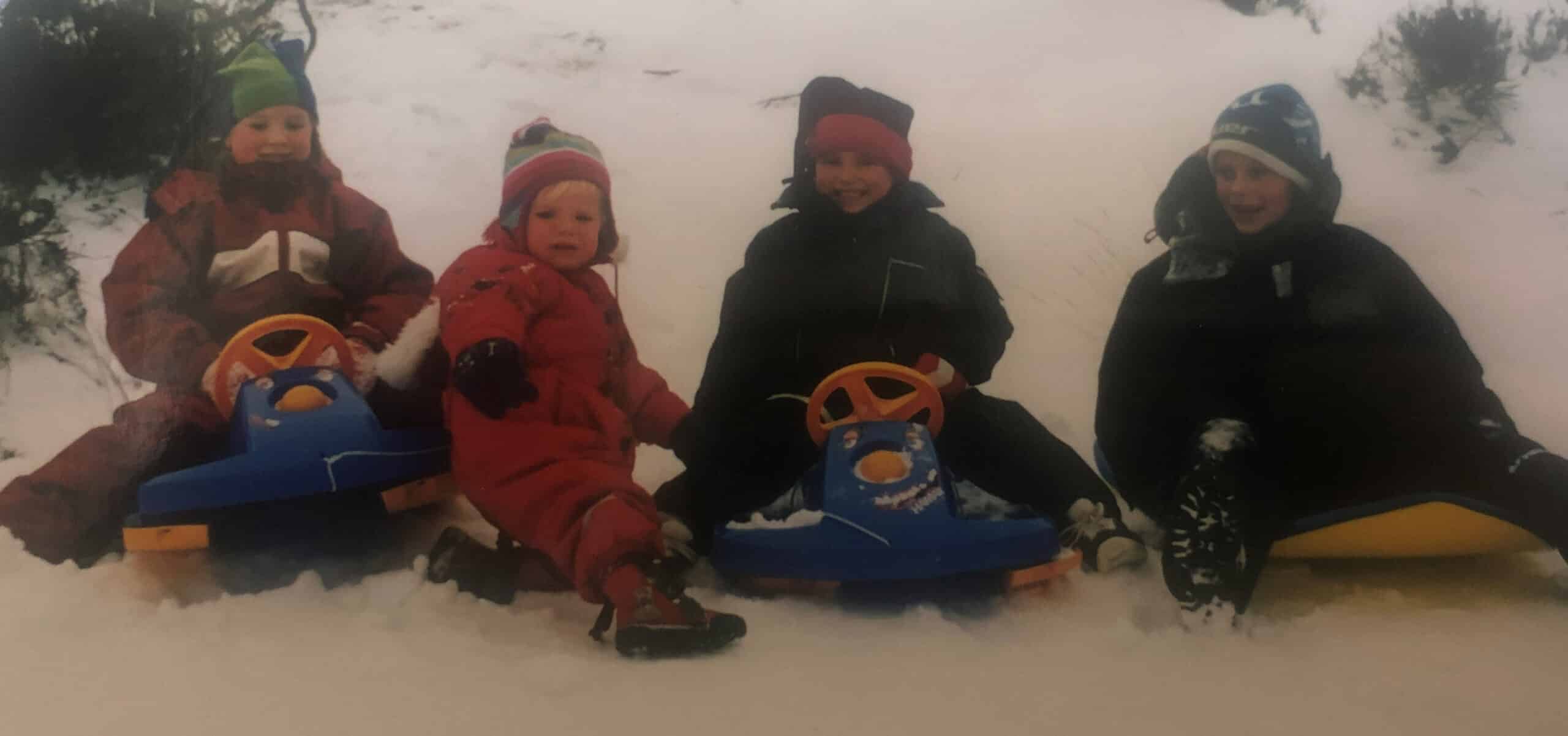

All through that spring and summer, Vegard went through gruelling chemotherapy. At times he got better, only to get worse again. The following summer, he received a bone marrow transplant from his little sister at the Rikshospitalet in Oslo.

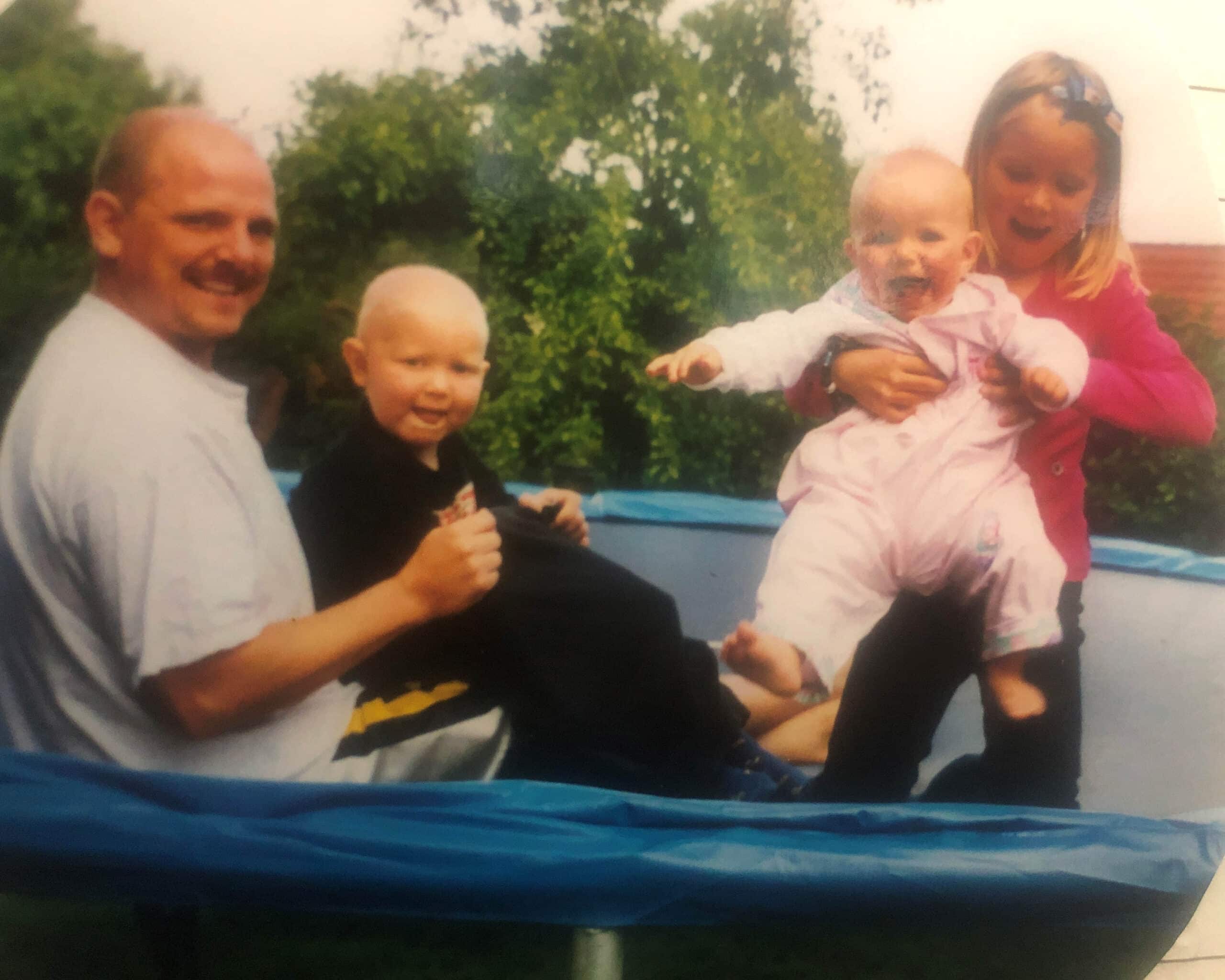

Back in Stavanger, Vegard, whose immune system was severely compromised, had to be kept in isolation. He spent most of that time on the trampoline in the garden, building up his strength as he had done many times before. It was pleasant and warm in the garden. People visited. No cancer cells could be detected in Vegard’s body. Would he pull through?

Heartbreaking question

Summer turned to autumn. Holidays turned into weekdays, and on one of those weekdays towards the end of November, the hospital phoned. They had discovered new cancer cells in Vegard’s bone marrow.

Once again, the family packed themselves into the car and drove all the way to Haukeland. Yet another full-throttle trip to the hospital filled with uncertainty, insecurity and fear.

When they got to the hospital, a brutal message was awaiting them: – We’re sorry, but there’s nothing more we can do.

A film script with such a merciless plot would be rejected. It would be too much. But the next chapter in our story would confirm that real life is stranger than fiction.

Ellinor tells us that the hospital told them to drive safely.

So that was what they did. They turned the car round and drove home again. Vegard fired questions at them from the back seat, the way five-year-olds do, and one of them was about the hospital buddy he’d lost a little while ago. Where had he gone?

– He’s in heaven, Ellinor said.

– Am I going to die too, Mum? Vegard asked.

– Yes, Ellinor replied.

And then came the question that became etched in their memory forever.

– Do they have beds in heaven?

Find a way out

On that September night in 2017, Rune and his companion walked lap after lap of the track in Randaberg. Rune talked about Vegard, how he’d fallen ill, and how they were going to lose him. But Rune had more to tell that night, more laps to do.

It was there and then, when Vegard asked his inconceivably heartbreaking question in the car on the way home to Stavanger in late November 2002. Rune felt desperate, and just wanted to find a way out. Even now, almost 20 years later, you can hear some of the desperation in his voice.

– I didn’t even tell Ellinor until years later. But back then, if it hadn’t been for our girls, I would have driven off the road. Just like that. There and then, in Stord, I would have driven the car into a cliff or into the fjord, Rune said.

Instead, Rune did what the doctor had told him. He drove safely. His family had no time to lose. Would Vegard make it to Christmas? They didn’t know, so the only sensible thing was to open their Christmas presents straight away.

– And then we went and watched Harry Potter. I’ve hated Harry Potter ever since, Ellinor said.

Plenty of time to cry

The same day, Rune got in touch with one of the doctors in Eastern Norway who had treated Vegard earlier. Was there anything at all that he could do?

The doctor put together a package of drugs, treatment that would help Vegard live longer. The result was six months at the end of Vegard’s short life that were filled with quality. What did that mean to Rune and Ellinor?

– It meant so much, Ellinor says.

– So much, Rune echoes.

All through the winter and into the summer, their boy was really well. During a trip to the cabin one weekend, the big lumps in the lymph nodes in his neck disappeared. On the way home, they stopped to eat pizza, and the boy who had hardly eaten for years, put away more pizza than he ever had before.

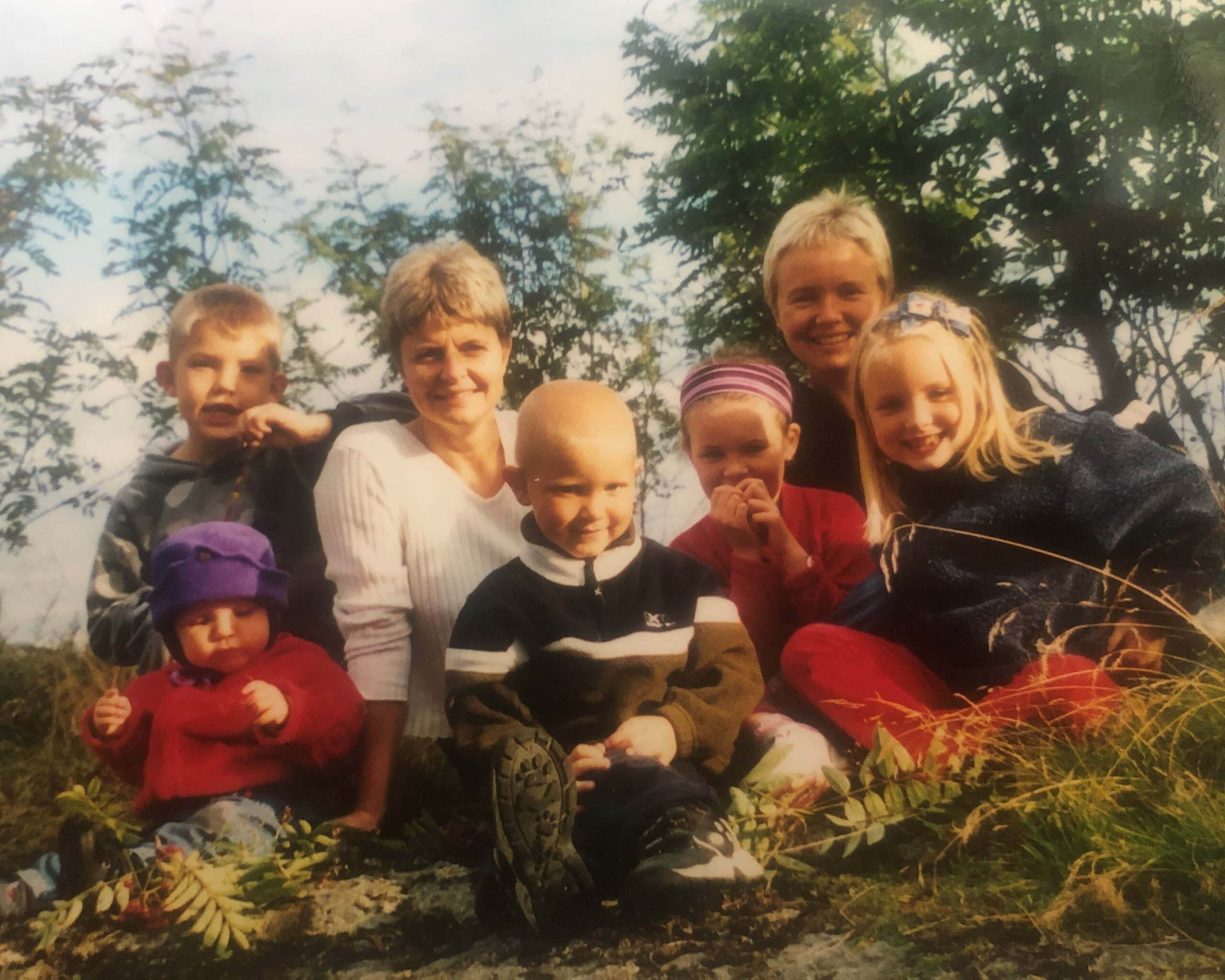

The last times became the best times. Vegard looked healthy. He went to kindergarten, he started school.

– We felt a bit like a normal family. If we weren’t normal inside, at least we looked normal on the outside, Rune said.

– There’ll be plenty of time to cry, said Rune’s sister, when well-meaning medical staff thought that the family didn’t seem to realise that they were running out of time.

– We couldn’t waste all that time crying. We had to live life with the kids we had, and that’s what we did, as much as we could, Ellinor explained.

And with that outlook, the little family crammed as much as possible into its life, until Vegard once again got worse, and finally died in September 2003.

New purpose

They walk together in silence, around the curve and into the straight. Rune continues. He asks his nocturnal companion: – Are we done?. But they aren’t.

In the hospital corridor, Rune is slumped on a chair, feeling completely empty. It’s August 2003, and he is going to lose his son. In the same hospital, a bit further down the same corridor, Rune’s father is on his deathbed.

– They died within a month of each other, my father one month before Vegard. I was just running from one deathbed to the other, Rune explains.

A film script with such a merciless plot would be rejected. It would be too much. But the next chapter in our story would confirm that real life is stranger than fiction.

Heads down and just get on with things

In 2007, Rune is out driving again. At the Mosvang campsite, he has to swerve the car into a bus lay-by, jump out and throw up behind a tree. This overwhelming nausea is not his body’s reaction to food poisoning or gastroenteritis, but is because of the chemotherapy he’s just received at Stavanger Hospital. It wasn’t just a blockage or constipation. Rune has cancer.

– Are you okay? a lady asks.

– Yes, I’m fine, Rune replies. He drives home and gets into the bath with a Jägermeister.

The next day, he goes to work.

Rune, poor guy, was never really allowed to be ill. It was only when we joined the Relay for Life that he was allowed to have his own disease story.

When Rune was diagnosed with bowel cancer in 2007, there was no denying that he felt both anger and injustice. He had lost his own son. Wasn’t that enough?

– We’re just not that good at giving up in this family, you know, Rune says.

– One fine day, some personalised treatment will come along. I just hope that it will be before I’m gone. That’s the straw I’m trying to hold onto, Rune says.

Rune and Ellinor. They’ve always been able to get back on their feet again. He’s had the same approach to his own disease. That it is something they have to fix. In the 14 years between 2007 and now, he can count on one hand the weeks he’s called in sick.

– I guess you could say that we’re at our best when we put our heads down and just get on with things.

Didn’t talk about the disease

We have a bit of a laugh at Rune’s macho routine – his Jägermeister after every chemotherapy session. He wouldn’t let himself be poorly for very long after the sessions. His wife wouldn’t let him, either.

The family was always very open about Vegard’s disease. They were always willing to talk about it, and their door was always open – even in the days after he died. Anyone who wanted could call in and spend time with him down in the basement. But everything was different when Rune became ill. Ellinor and Rune didn’t want to talk about it and were only open with their friends and closest family. Ellinor dragged her husband out on walks around the area, just to show how well he was. They were doing it mainly for the kids; there were loads of stories about people who had discussed Rune on the bus, the bus that their own kids also took.

– Rune, poor guy, was never really allowed to be ill. It was only when we joined the Relay for Life that he was allowed to have his own disease story, Ellinor says.

Out cycling

It’s early morning, almost four o’clock, and the skies above Randaberg will soon start to grow light. It seems to be doing him good to be walking here and chatting – albeit with a guy who was a complete stranger just a few hours ago. They do a few more laps.

Fast forward to 2012, and the family Lunde had started to relax a little. Five years had passed since the diagnosis, and the doctors could find no cancer in Rune’s body. Everything was looking great.

Seven years earlier, the doctors had operated to correct a congenital problem in both of Rune’s hips. His rehabilitation involved cycling, and he’d done a lot of that in the last few years.

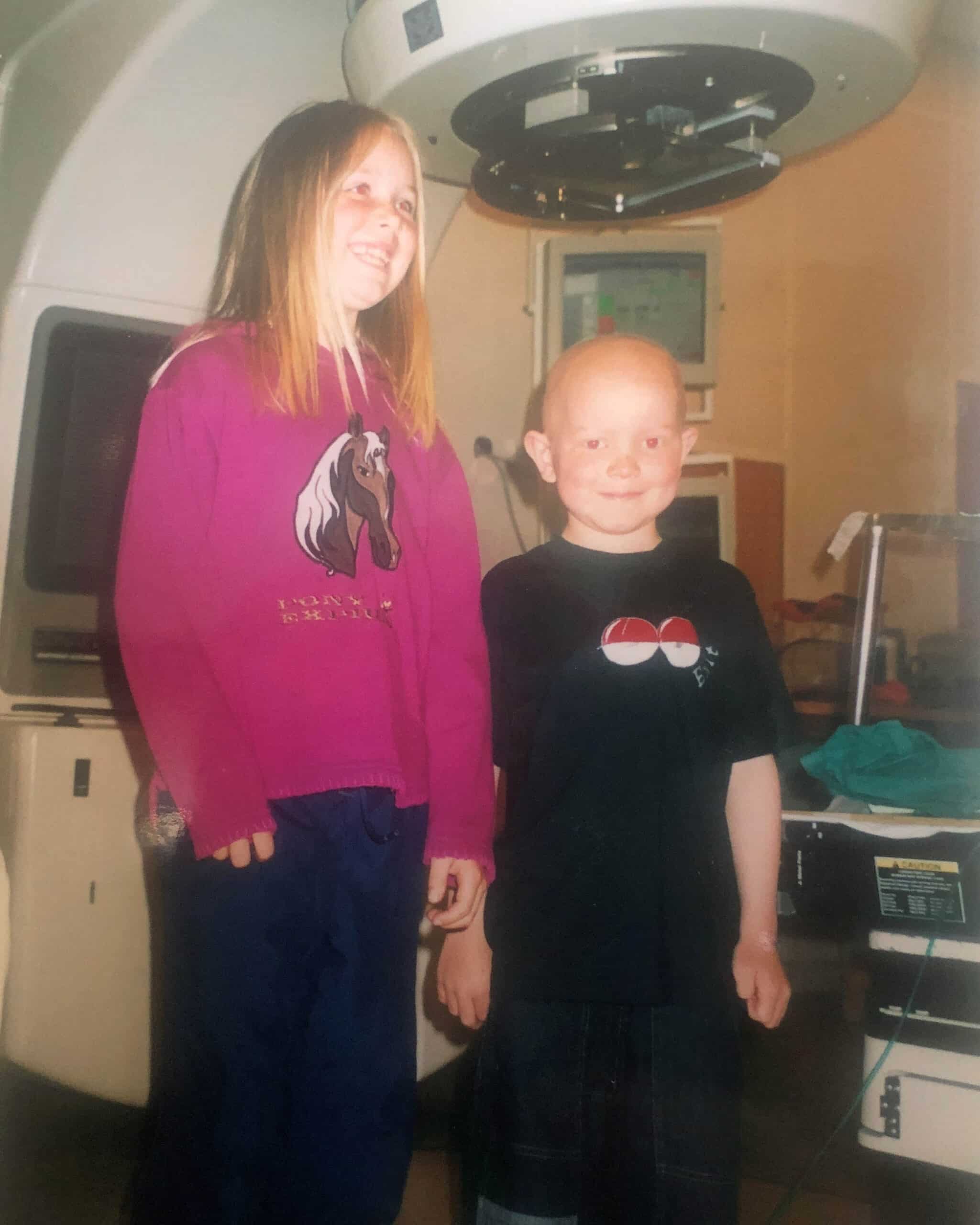

When he felt pain in his groin in 2015, Rune assumed that it was because of the cycling. The doctors thought it was a hernia. They operated, and Rune started cycling again. But the images did not reveal a hernia, but cancer, that had spread to his groin and into his hip bone. Rune underwent radiotherapy. He then had surgery, got back on his feet again, and continued with a new lease of life.

Relay for Life

– I remember Ellinor picking me up at the airport and telling me about a Relay for Life event they were going to have in Randaberg, and that they were planning a kick-off meeting. We could pop in, I said.

‘It’ll just mean something like standing on a roundabout as a marshal,’ Ellinor thinks. Because, you know, it’s a relay race.

The first meeting went down in history. Rune had just had a hip replacement in one of the problem hips, and right there in the middle of the meeting, it popped out of its socket.

– There are people here from the Norwegian Cancer Society, and people who have come all the way from the States. And there I am, being stretchered out to an ambulance.

Ellinor and Rune both laugh loudly.

But Rune got back on his feet and signed up so that when the Norwegian Cancer Society organised the first Relay for Life in Norway, in Randaberg in September 2017, Rune Lunde was the logistics manager.

The event was pivotal for Rune and Ellinor. It gave them the opportunity they both needed to open up about Rune’s disease.

Whether I have five years, two years, one year, I don’t know.

– It’s about meeting like-minded families who are going through the same thing. Meeting someone who is on the same half of the track as you are, who understands what you’ve been through and knows what you’re facing. Before, I would try to hide the fact that I was ill. Relay for Life helped me to be more open about myself and my disease. Relay for Life gave me a purpose. And it gave Ellinor a purpose too, Rune says.

With their friends and relatives, Rune and Ellinor joined up as the Squirtle team, named after Vegard’s favourite Pokemon. Rune walked the first lap with around 50 other so-called fighters – men and women who either had cancer or had survived the disease.

– That first lap was nothing short of magical, Rune says.

The Norwegian Cancer Society’s Relay for Life can neither cure the disease nor take away the grief and pain. But meeting like-minded people can take the pressure off and help people breathe out and find new purpose. Rune Lunde knows that. Photo: Olaf Grodem

When the night was over and the event had finished, Rune was convinced that this was something he would like to help others to share.

– I was asked to be a leader, but I thought I’d turn that down. Ellinor thought I should accept, so I did, he tells us.

In 2018, the event moved indoors. Ellinor had the dubious pleasure of keeping control of 50 kids in the queue for the bouncy castle. She will never forget when her eyes met those of one little boy. – Look at me, his eyes were saying. – Aren’t I good? All the work they had put in, all the hours of missed sleep – when she saw the pleasure on that little boy’s face, she was in no doubt that it had been worth all the effort.

– Maybe he had a mum or a dad, a grandmother or a sibling. Maybe this was the really cool thing that this boy got to do that week, that month, that year. I have no idea. But for me, he became a symbol of this as a sanctuary, Ellinor tells us.

About the Norwegian Cancer Society’s Relay for Life

- Relay for Life is the Norwegian version of the American Relay for Life, which was started by the doctor Gordy Klatt in 1985. It is now the biggest non-profit event in the world.

- For 24 hours, teams made up of families, friends, schools, societies, workplaces and others take part in a relay. Behind each team is a story – a person who the team wants to support or remember.

- Fighters, people who have or have had cancer, are the relay’s guests of honour, and are invited to a separate programme in the relay.

- The relay symbolises the fact that the disease of cancer never takes a break, but is there day and night, so there should always be someone on the course for the person who is sick.

- The event is a relay involving different sized teams, in which the participants do not walk or run against each other, but alongside each other.

Uncertain times

Relays are relays – but life is something else. In 2019, Rune’s cancer had spread to his peritoneum. Hot chemotherapy treatment applied directly in the abdomen meant that all Rune could do was lie on the sofa. For a long time. He lost 10 kilos, and looked like an old man overnight.

– If you were told you had to do it again, I think you’d look for that same way out as you did on that journey in Stord, Ellinor says, remembering the drive home from the hospital when they had to tell their son he was going to die.

– You’re right, I was really fed up, Rune says.

In 2020, the cancer had spread to his lungs, first one and then the other, and now, after we finish talking, he’s waiting to find out what will happen next. What the next life-extending treatment will be. It could be more radiation, or perhaps yet more surgery.

Which emotion best describes the situation? Is it anger? Fear? Despair?

– We sat out here one evening, we had a fire going in the firebowl, I think it was a Friday. We were talking about it then, that I’m hoping to see my grandchildren. That’s the hardest thing to deal with. Whether I have five years, two years, one year, I don’t know, Rune answers.

When the diagnosis was confirmed in 2007, the doctors gave Rune five years.

– What would have happened if we’d given in to it then?, Ellinor asks.

– It would have proved them right. But we kept going so that Rune would get the best treatment possible. That has really made a difference. We can’t focus on the end, because the end will come.

Honour and prestige

One Saturday in March this year, Rune was busy in the kitchen. Their eldest daughter was coming home with her new boyfriend, and they wanted to make a really nice dinner. Ellinor put the best white tablecloths on the table, and there seemed to be no limit on how much food they were preparing. I know we want to make sure there’s plenty, but this is a bit over the top, Rune was thinking.

Then the doorbell rang, and even though he was right in the middle of cooking, the others seemed to think that he should be the one to go and answer the door. Strange.

Standing outside were the Norwegian Cancer Society’s Relay for Life manager Lars, and district manager Camilla. They had also brought a photographer.

It turned out that they were on a ceremonial errand, and that everyone had known about it except Rune. Rune had been awarded the Global Recognition Award by the international Relay for Life Foundation, for his extraordinary efforts for the Norwegian Cancer Society’s Relay for Life. For his accommodating attitude, positivity, get-on-with-it spirit and ability to get things done. For all the days and weeks of voluntary work he’d put in, despite his own disease.

– I just broke down when they turned up with that award. It means such a lot to me, Rune says.

It may have meant just as much to Rune that both his girls put everything to one side and were never in two minds about whether or not to come home and make a fuss of their father that weekend.

There is a future

Uncertain about what the future might bring with his disease, Rune and Ellinor have stepped aside. Younger reinforcements have taken over the relay baton, but the couple enjoy acting as ‘senior consultants’ if any questions arise. They are both happy that Relay for Life is in safe hands and will carry on with even greater ambition. Rune’s own ambitions are to live a good life for as long as he can. And in the hope that new developments in treatment will catch up with the progression of his own disease.

– Cancer is an incredibly important issue. Imagine, one wonderful day, that even though you know you have cancer, that there are medicines that can cure you. That’s something to aim for. I hope it will happen.

– That’s what I feel that the Norwegian Cancer Society is saying to me right now. That there will be a day when no one ever dies of cancer again. Such visions and goals are important to hold onto, even if this won’t happen overnight, or the night after that, Ellinor says.

On the running track in Randaberg, the nocturnal companions thank each other for the walk and conversation. They think that it’s wonderful that the Norwegian Cancer Society has organised the Relay for Life. That there’s always someone on the track for the people who are gone, for the people who are fighting, for the people who will survive. They all have a burden to carry, but just now, it’s a little bit lighter.

And now day is breaking in Randaberg.

We’re sharing our story because we want to help raise awareness about cancer issues and attract more members and more funds.

Rune

Photo: Desiree Photography Stavanger, Olaf Grodem and private photos.